John Howard and Narelle Kennedy, 3 October, 2024

Everywhere wants to be the next Silicon Valley, a rich concentration of advanced technology enterprises, entrepreneurs, world-class universities, and researchers that attract global talent and investment, quality jobs, and high-growth industries.

Promoting high-tech innovation districts, precincts, and hubs is a favoured strategy by economic development professionals and organisations.

They are vital innovation ecosystems, fostering creative and entrepreneurial endeavours, enhancing economic prosperity, and achieving urban and civic renewal.

However, while innovation districts represent economic vitality and progress, they also have significant and often unrecognised shortcomings that undermine social well-being and cohesion.

It is time for more robust questioning of high-tech innovation districts and similar clusters, marshalling the research on their common pitfalls and finding ways to redress these deficiencies.

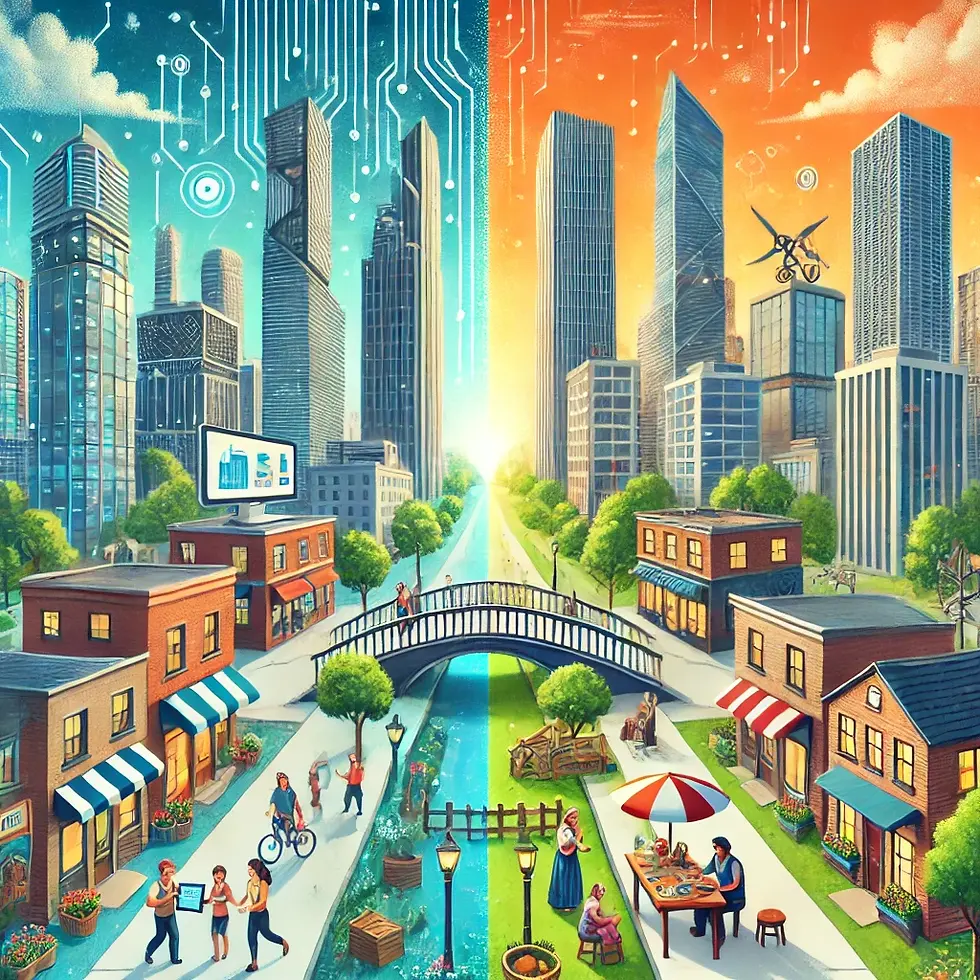

It is time to re-think place-based innovation policies, the essential feature of which is connecting economic development with community development.

Scepticism about Silicon Valley

A range of researchers argue that there are limitations to the positive spillover effects of Silicon Valley as a high-tech innovation district. This is the case despite Silicon Valley’s wider economic benefits from fostering research-rich entrepreneurial start-ups, new jobs and industries and creating tech giants like Apple.

They point to significant inequities: wealth concentration among a small elite, high housing costs, environmental stress from excessive energy consumption and waste generation, and wage stagnation for non-tech workers.

The economic benefits are not universally shared, and employment opportunities are skewed towards those with high educational attainments, widening the gap between skilled and unskilled workers (Florida, 2017; Glaeser, 2011; Markusen, 1996; Autor, 2015; Bulkeley et al, 2011; Moretti, 2012).

Other commentators like Tom Foremski, the publisher of SiliconValleyWatch.com, argue that innovation is restricted as Silicon Valley has become insular. While Silicon Valley is a place where start-ups can scale their business, it is no longer the place for sourcing innovative ideas, because of its “self-segregated business park monoculture”.

Foremski contends that Silicon Valley employment practices insulate their people from everyday struggles, resulting in essentially frictionless, predictable living for Silicon Valley creatives. Hence, no motivation for original ideas generated by experiences of diversity and adversity.

Gentrification

Another downside of high-tech innovation districts is that they trigger gentrification.

New infrastructure investment and the influx of high-income knowledge workers and their high-paying jobs elevate housing costs and property values. This can be exacerbated by speculative investment and local decision-making favouring corporate interests.

The effect is that longstanding residents, often lower income families, are displaced as rents and essential service costs increase. (Lees, Slater and Wyly, 2018; Fields, 2015).

Social Inequality & Exclusion

Innovation districts aim for major economic restructuring and are disruptive by definition. They seek to transform places and to create new jobs, industries, skills and opportunities, consequently attracting newcomers different from the existing population.

Inevitably, a two-tier labour market emerges, where high-income professionals and low-income service workers co-exist but with disparate economic and social prospects.

Inequality is also evident in the disproportionate focus on advanced technologies and new-to-the-world breakthroughs and the influence of already powerful interests, like property developers, in shaping the composition of innovation districts.

Little attention is paid to non-technological innovation and the ingenuity of mainstream businesses. (Brown & Greenbaum,2017).

Finally, innovation districts are typically judged on economic and commercial returns, to the exclusion of social innovation and benefits to the wider population. (Bourdieu, 1986; Granovetter. 1973).

Loss of Community Identity

Innovation districts are rarely initiated or controlled by local people. They feature global businesses and a mobile cosmopolitan population with different socioeconomic profiles to the local community.

Global retail chains and brands replace local traditions, landmarks and businesses, diluting local and indigenous cultures and distinctiveness (Shaw & Hagemans, 2015; Zukin,1995, 2010).

There is a loss of a sense of belonging. Invisible assets like community relationships, values, and local vernacular are diminished. The collective cultural memory and sense of place fade, replaced by a narrative of tech-driven progress and competitiveness (Harvey, 2008). Existing residents, lacking the financial or educational capital to adapt, become cultural ‘outsiders’ in their neighbourhoods (Butler, 2007; Slater, 2006).

Saving Innovation Districts

Innovation districts can still drive economic growth and prosperity but should not do so at the expense of social equity and community cohesion.

Rather than abandoning innovation districts, they require a re-think. Building on their foundation aims of boosting place-based economic development, innovation districts should expand their remit to advance community and social wellbeing also.

Action is recommended on three fronts:

Invest in innovation at the level of the enterprise and the workforce. Build their innovation management capabilities for solving problems and responding to opportunities that matter to customers and communities. Don’t be satisfied just with increasing the supply of advanced technologies.

Ensure the benefits of innovation reach beyond knowledge workers and creatives to the wider population, including those most likely to become the casualties of economic disruption. Start by including the everyday economy and essential workers as a key target in innovation strategies, as a cross-over between economic and community development plans. Participate in projects on place-based capital and community wealth building.

Promote use of social and community wellbeing measures in evaluating economic development projects in high-tech innovation districts. Emphasise local community engagement and co-design. A useful tool is the Cities and Regions Wellbeing Index for 2024 by SGS Economics and Planning.

The aim is not to copy Silicon Valley but to create and sustain vibrant innovation districts that are great places to work, live and play.

#InnovationDistricts #SocialInclusion #EconomicDevelopment #CommunityEngagement #Gentrification #TechHubs #SiliconValley #UrbanRenewal #SocialEquity #EconomicProsperity

*This is a summary of an article by John Howard and Narrelle Kennedy, published in the current issue of the Economic Development Journal on the topic "The Power of Place." The article includes a detailed bibliography.

The article can be downloaded here:

Comments